We are all too aware that we find ourselves in an unprecedented global crisis due to COVID-19.

As a child therapist who uses the Violet Oaklander Model of Gestalt Therapy with Children, I wish both to gather and to share my thoughts about employing it with children and families in this particular time of social distancing and virtual therapy. I have had the privilege of sharing this model with a number of talented, wonderful child and adolescent therapists in Italy whom I’ve known for the past 7 years. and my heart is with them and the children they serve.

The article presents a case example to define, explain, and illustrate use of the Oaklander Model in a telephone or online session and by deploying technology to see a child’s projective work. It begins with concepts basic to the model, includes brief descriptions of children’s varied coping strategies and therapeutic responses to them, and offers specific pointers for telephone or online sessions. Then, the case study of 10-year-old “Mary” shows how current technologies and classic Oaklander techniques—the practical and the projective—might be applied under extraordinary circumstances. I thank Mary and her family for graciously permitting me to reproduce her session notes, words, drawings and likeness to illustrate the use of the Oaklander Model in a time of crisis. Finally, the article suggests further session activities.

The article’s title, “Just for Now,” immediately suggests a way to frame therapy during this time. It reminds therapists and families that we should now embrace crisis-oriented goals and interventions that strengthen children’s sense of self and resilience, and that we should postpone any deeper work to help them respond to the immediate situation—the most relevant and ambitious task we have.

Therapist-Child Relationship

Especially during stressful periods, the therapist-child relationship is paramount. For that relationship to maintain its authenticity, tell children the truth about what is happening in developmentally appropriate terms. That is, ensure that the information shared is titrated to what they need to know for their health and safety but is appropriate for their level of maturity. First, ask parents to find out what children have already heard in the family, on TV, or outside. Second, don’t assume children actually understand what they have overheard. They may have only processed only the stress and remain confused about the facts and what they mean for their lives. You will now be able to inform them in a manner they can grasp and that supports their resilience.

Heightened Challenges of Contact

Contact in Gestalt terms indicates the ability of the client to be present—to utilize physical, emotional, and intellectual powers to connect with the self and other in the present. Clearly, limitations on our physical presence in a session raises special challenges.

On the most basic level, sessions may need to be shorter to accommodate children’s shorter attention spans when they’re viewing us on a screen. If it’s appropriate for a parent to be involved in your work with a child, that presence might increase the child’s focus. For example, the session with Mary, discussed below, included her mother and, briefly, a sibling.

Egocentricity: Avoiding Guilt Feelings

Typically, developing children are egocentric and tend to blame themselves for misfortunes—if not for a global pandemic, perhaps for some aspect of it. If a family member or a teacher gets sick, they might feel responsible for not washing their hands enough. Tell the child that this isn’t her or his fault, and encourage parents to do so as well.

Prioritize Therapeutic Tasks

Reshape you working with a family during this crisis by prioritizing basic necessities: everyday logistics and working together as harmoniously as possible.

In addition to your work with the child, be open to helping the family make a plan to get through the crisis.

Remind the family to set aside their differences Just for Now. In addition to COVID-19, a family may be coping with significant other issues, such as divorce, loss, or trauma. In addition, families may now be dealing with financial and emotional strains from sudden unemployment, having to leave school or other programs, or cancelled events and outings. Whenever possible, encourage families to focus on surviving the present crisis without disrupting interrelationships and daily life.

Set Aside, but Adjust for, the Presenting Problem

Appropriate response to a crisis might mean that the therapeutic goal of treat the presenting problem should be moved aside Just for Now to help the child and family navigate current pressures. Of course, the presenting problem will be a factor in how the child reacts to the crisis.

Different presenting problems may manifest with different characteristics in a crisis. To name only a few examples:

Anxiety: may display as excessive worrying, to the exclusion of anything else

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: already stringent sanitary practices may become even more extreme, especially given official urging to wash hands and surfaces well and often

Depression: may lead to shutting down, withdrawing, or anger

Denial: may encourage carelessness because “This is an overreaction,” “I feel fine,” “I’m washing my hands, so I won’t get this virus, or spread it.”

Anger: may erupt as “This isn’t fair,” “I hate this.”

You can manage each type of reaction. First, validate all response styles – everyone is stressed.

Children’s behavior during stress and trauma is their way of trying to get their needs met.

If you consider their individual response in the light of their individual needs, you can provide them with specific and more appropriate ways to cope.

In the midst of a crisis, parents often feel they lack the emotional strength to tolerate their children’s expressions of their worries and resentments. To help, coach parents to schedule a timed, 1-5-minute “gripe session” to let their child air all complaints and concerns, and to curtail constant outbursts. Direct parents to stick to the following rules:

Just listen—no interrupting, and no arguments about the content.

When the timer goes off, move onto the next item on the schedule parents have created, possibly with your help.

When worries come up at other times, parent offers to make a note of it for the next scheduled “gripe session.”

Therapeutic Response to Anxiety

Validate the worry

Everyone’s anxious about a pandemic!

Schedule a daily but time-limited “worry session.”

Recall that anxious children often benefit from the chance to express their aggressive energy.

With parents, make a list of what is possible at home

Children can rip up a magazine, stomp on the floor, do an exercise video, punch a pillow, etc.

With this information, help children make a list of which activities they would like to do at home.

Therapeutic Response to Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Validate the need to feel clean and be hygienic.

Review with the child the CDC guidelines and the supplies in their home, and how to follow the recommended practices.

When the child feels the need to do “more,” reassure and remind him or her that the recommended measures that have been taken, then go to the next scheduled activity.

Follow the same guidelines for responding to Anxiety.

Therapeutic Response to Depression

Prioritize the treatment for improved well-being Just For Now.

Postpone treatment for deeper issues.

Schedule a worry session, and include feelings of sadness and hopelessness as topics.

Schedule a gripe session to allow and encourage expressions of anger.

Follow a schedule.

Encourage everyone in the house to get up and dress in everyday clothing and follow the regular household routine.

Therapeutic Response to Denial

Recall that denial is a form of resistance and an important coping mechanism in response to overwhelming stress and trauma.

Respect this need in children and follow the necessary guidelines for health and safety without over-explaining.

Remember that children do not need to know all the facts adults must know regarding this crisis.

Therapeutic Response to Anger

Recall that anger and aggressive energy are valid, important emotions for children to experience and express, especially during crises.

Make parents aware that, as with all reactions, anger is a way children are trying to get their needs met as they process stress and fear.

Validate the anger:

”I am sure you’re angry at this COVID-19! Or me, or….”

Schedule an uninterrupted gripe session.

Make a list of acceptable angry actions: punching a pillow, ripping up a magazine, going into another room to yell, etc.

For yourself, here are a few pointers about anger:

The fear associated with COVID-19 is likely to cause household tension. So parents may have even less tolerance for children’s expressions of strong emotions. Therapists’ validation of the anger reaction and guidance finding ways children and other family members can express it lets everyone feel heard.

Help Families Set Limits to Reassure Children

Therapists and parents want to ease the pain children feel in difficult times. Remind parents that children feel safer with appropriate limits and boundaries. Encourage families to write down the schedule of the usual home routine especially in this unusual period. Then, be sure to include things important to children’s development and calm, such as

Preparing and eating healthful foods

Exercise

Regular chores

Homework

Family time

Social time (online for now)

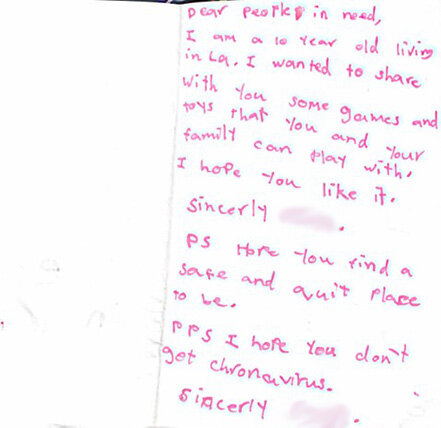

Activities that give children a sense of purpose. (For example, Mary cleaned her closet of toys for donation to a children’s charity.)

Fun things to do

You can encourage children and families to document, with drawings or photos, how they follow the schedule, as Mary and her family did.

Use the Polarities

A crisis evokes extreme emotions, mostly negative. These all-encompassing negative feelings can overwhelm children and families. Being sensitive to polarities–views of the self that are split into opposites of “good” and “bad”—can facilitate expression of fear, anger and sadness, and can validate those feelings as well as balance them with memories of happiness. This balancing helps change their perspective and even reduce stress.

Tips for Phone or Online Sessions

Don’t be daunted by this format! Remember that most children of all ages are quite tech-savvy, comfortable learning new technology, and already adept at socially interacting by FaceTiming with family and friends.

Pre-Plan

Because you aren’t in your office with all your supplies, pre-planning is important. For instance, I told Mary and her mother—in advance of the session—to set out markers, paper, magazines and books, and to be able to get photos from her mother’s iPhone as we were working.

In addition, parents need to provide a private space and quiet time for the child’s or adolescent’s virtual session. With everyone at home during this crisis, flexibility is essential. For example, Mary’s older sister came in for part of the session but left when Mary asked her to, so she could make her “worry list” by herself.

Pacing

Assessing contact—the client’s ability to be present—is more difficult virtually. So keep in mind a choice of engaging activities in case the child loses interest or works more quickly than anticipated.

In Mary’s case, I elected first to have her make 3 drawings, which is more labor-intensive than selecting images, the technique I switched to for the Happiness part of the session. This change was designed to prevent her from tiring of drawing and to retain her interest while still experiencing the polarities. If I had noticed she was tiring of either activity, I would have asked her to find toys or objects that could represent her memories.

Be prepared for shorter sessions if the child or adolescent is less engaged with this format. When possible, end even a briefer session on a positive note highlighting what the client accomplished.

Include Parents Who Would Aid in Transitions

Since this was a first virtual session, and I knew the relationship between Mary and her mother to be very positive, I elected to involve her in this session. As this one was successful, later sessions might include just Mary.

In future weeks, I will be documenting sessions with teens, who were, as might be expected, completely comfortable with the online format without their parents.

Use the Family’s Home as a Resource

For therapists who primarily see children and adolescents in a clinic, school or private practice, this crisis offers an opportunity to use the client’s home as a resource.

Have them give you a tour of their home, introduce you to their pet, siblings, other household members, and special places or objects.

This tour gives you a way to use their senses:

What are the most common, favorite, and least favorite sounds of their homes? They can tell, write, or make those sounds for you.

Expect sounds such as their dog barking, sibling yelling, traffic, music, or preparing food.

Work with adjectives: Are the sounds loud, quiet, musical, muffled, calming, upsetting?

What are the most common, favorite, and least favorite sights in their home?

They can take you on a tour again, perhaps of their room or favorite space.

Work to increase expressive spoken or written language to describe their room or favorite spot: Is it warm, cool, quiet, private, shared, small, large, comforting, exciting?

Follow the same guidelines for the senses of touch, smell, and taste:

What are the most common, favorite, and least favorite things to touch in their home?

What are the most common, favorite, and least favorite smells in their home?

What are the most common, favorite, and least favorite tastes in their home?

Case of Mary

Ten-year-old Mary’s strategies for weathering this crisis had become a bit obsessive:

Over-focus on handwashing

Worrying about unclean door handles

Forbidding others to touch her objects or playthings

During the session I deliberately kept the tone light in response to the intensity of the crisis we are all experiencing. It included solution-oriented steps, such as a Worry List and gripe sessions at home to enable her to express her worry and to come up with action steps that would promote positive feelings. Mary was also encouraged to set up a schedule to structure her time while at home, which included exercise, chores, socializing and a chance to help others.

Mary’s “Worry List”

Mary’s Schedule:

Exercise

Project with a Purpose

Mary’s Fun List

Using the Polarities

Peter Mortola, professor at Lewis and Clark University and author of Window Frames, noted that generous acts such as Mary’s donating her toys to other children was a helpful polarity to the social distancing mandated by this crisis. That is, it allowed Mary to recognize she herself could balance out the evil of that isolation was with her sharing. I was able to use polarities revealed by projective exercises to the same effect.

Projective Exercises

By FaceTime, I asked Mary to make three drawings, and asked her and her mother to email them to me:

A memory of feeling worried from when she was more than a year younger

A memory of feeling worried one year ago

A memory of feeling worried during the past month

Then I asked her to rank each of her chosen memories in order of how strongly she felt at the time. Finally, I asked her to let me know why she had ranked each memory as she had.

The purpose of having Mary make these drawings, rank them and then explain them was to give her opportunities for connecting to other times she had feelings similar to those she has now. She and her mother decided to title them for clarity. As a result, she could see that the feelings are familiar and that she has lived with them. asking her to choose which occurrences of fear and happiness she would draw let her express and strengthen her sense of self, a therapeutic goal of the Oaklander Model.

Drawing #1

“This is Me Having my Heart Surgery When I was 3.”

Drawing #2

“This is From 2019 When People Weren’t Nice to Me.”

Drawing #3

“People who have Corona Virus”

I then asked Mary to rank her drawings from the one she had the strongest feelings about to the mildest. She had the strongest feeling about her early childhood drawing of having heart surgery; her middle choice was her drawing about the Corona Virus; and she had the mildest feeling about the drawing of people not being nice to her.

When I asked why she made these rankings, she said:

Because it’s really scary having surgery and you have something in your body that’s unusual.

And it’s not very regular. Most people don’t have it. Ever since then I was afraid of shots.

They had to stick a needle into me. Ever since then I’ve been terrified.

Mary’s mother was surprised that Mary had a stronger feeling about her earlier memory of heart surgery than about the current stressor, COVID-19. Mary’s ranking exemplifies the value of offering children the opportunity to express their own point of view without interference from an adult’s perspective. The pointer for therapists; Don’t assume that what’s foremost on our minds is what is on kids’ minds.

This exercise was followed by my asking Mary to pick three images which would represent the polar opposite of these negative feelings: memories of happiness that during the exact same time frames. Mary and her mother emailed these to me.

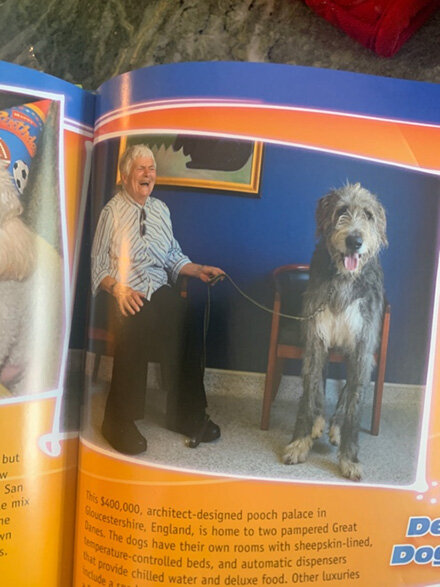

Image #1

“Happy Feeling When They Got Their Dog ‘Bubba’

When She was 8”

Image #2

“Happy Feeling when Mary Learned How to Solve a Rubik’s Cube”

Image #3

“Mary’s Happy Feeling in her Role as Yenta in ‘Fiddler on the Roof’”

When asked to rate her strongest to least strong feelings about her images, Mary ranked that of getting a dog as her strongest; playing Yenta in as second, and solving the Rubik’s cube as third.

I asked Mary to process her thoughts about the two exercises. She said:

I thought that you can change from worry to happiness–you never know if you could be happy or sad.

If you are doing something that you’re excited for, you don’t know what could happen—it could cancel.

I also asked if she noticed any difference in what she thought or felt when working with both emotions. She replied, I felt the same when processing both.

Reflections on the Session

This sample session illustrates a way to use the Oaklander Model in a crisis. It helped Mary identify and focus upon the feelings the current stressor elicited. In addition, it gave her a context of both similar emotions previously felt and of her experience of its polarity in past occasions of happiness. As a result, it reminded her that the worry she’s experiencing is “just for now.” Even in the midst of this crisis, Mary learned, she can experience joy and other positive emotions as well. She even seemed to have had the experience of processing both sad and happy memories with the same feeling, once the memories were seen from the perspective of the present.

Suggestions for Sessions

Have the client imagine a safe place, draw it, and describe it. The ability to imagine an internal safe place is especially important when our external world has become a source of uncertainty and danger.

Help the child identify and connect feelings with how and where they are in her or his body; “Where do you feel the worry in your body? What does it look like? Draw it, be it, and describe yourself as that feeling.”

Teach relaxation exercises such as visualizing pleasant imagery and relaxing the mind and body. There are many apps to choose from that are good for children.

Make a collage. Pick a theme if desired, and choose images from magazines to cut out, arrange and glue on a large sheet of paper or poster board. Encourage the child to describe the collage to you, and to see it as his or her individual creation of meaning.

COPYRIGHT 2020 KAREN FRIED